Our lab is interested in understanding the molecular mechanisms that control early development in vertebrate embryos. Specifically, we use chicken, quail, peafowl, and axolotl embryos as research models to understand cell fate and cell state changes during embryogenesis. We are interested in questions like:

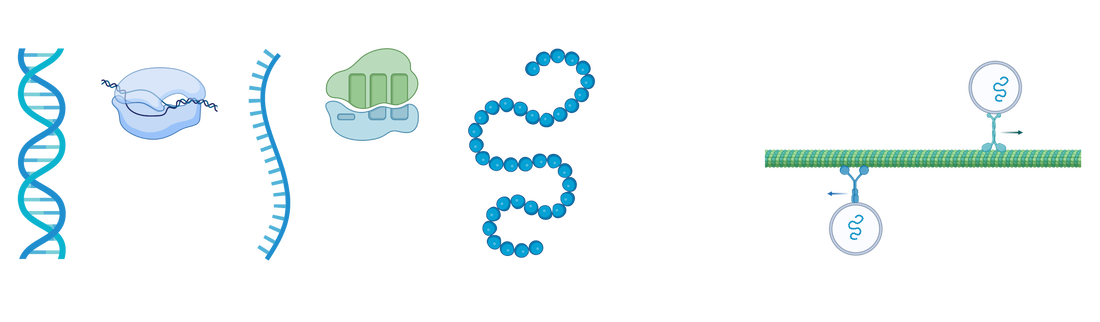

- How do cells know what to become? Are these decisions controlled at multiple levels (DNA-RNA-Protein)?

- How do cells know that they should stick together when other cells are leaving and migrating throughout the embryo? How is cell adhesion regulated (gene vs. protein)?

- How important are certain proteins to developmental processes?

- What makes cells unique within a tissue? Within an organism? In different organisms?

To answer these questions, we study neural tube and neural crest cells, which are ectodermal derivatives. Development of the progenitor (stem cell-like) cells that create the central (CNS, neural progenitors) and peripheral nervous systems (PNS, neural crest cells) is tightly linked. We want to know what makes neural cells neural, and what makes the neural crest cells that leave the neural tube different from the others. We are also interested in finding out why and how the cells that leave start migrating. The process where neural crest cells leave the neural tube is called the epithelial (adherent cells) to mesenchymal (loose cells) transition or EMT.

We believe that the strict spatial and quantitative regulation of transcriptional regulators and adhesion molecules during cranial neural crest formation, EMT, and migration allows this complex process to occur. My current research focuses on:

1) Characterizing the function of neural crest transcription, cell adhesion, and cytoskeletal factors during cell fate specification and EMT and identifying novel targets and co-factors.

2) Identifying the timing, function and regulation of the cadherin proteins during cell specification and EMT.

3) Analyzing the effects of cadherin protein changes on cell cycle, proliferation and differentiation.

4) Identifying the effects of exposure to teratogens dysregulates normal embryonic development.

Funding Sources:

1. NSF CAREER Grant , Functional Analysis of Crest EffectorS (FACES), 2143217 (2022-2026)

2. NIH NIDCR R03 Grant, Mechanisms of microtubule-mediated cranial neural crest EMT and differentiation, DE032047-01 (2022-2024)

3. RSCA Scialog Advanced Bioimaging, MRI with molecular specificity for a new realm of neurodevelopmental research (2022-2023)

- How do cells know what to become? Are these decisions controlled at multiple levels (DNA-RNA-Protein)?

- How do cells know that they should stick together when other cells are leaving and migrating throughout the embryo? How is cell adhesion regulated (gene vs. protein)?

- How important are certain proteins to developmental processes?

- What makes cells unique within a tissue? Within an organism? In different organisms?

To answer these questions, we study neural tube and neural crest cells, which are ectodermal derivatives. Development of the progenitor (stem cell-like) cells that create the central (CNS, neural progenitors) and peripheral nervous systems (PNS, neural crest cells) is tightly linked. We want to know what makes neural cells neural, and what makes the neural crest cells that leave the neural tube different from the others. We are also interested in finding out why and how the cells that leave start migrating. The process where neural crest cells leave the neural tube is called the epithelial (adherent cells) to mesenchymal (loose cells) transition or EMT.

We believe that the strict spatial and quantitative regulation of transcriptional regulators and adhesion molecules during cranial neural crest formation, EMT, and migration allows this complex process to occur. My current research focuses on:

1) Characterizing the function of neural crest transcription, cell adhesion, and cytoskeletal factors during cell fate specification and EMT and identifying novel targets and co-factors.

2) Identifying the timing, function and regulation of the cadherin proteins during cell specification and EMT.

3) Analyzing the effects of cadherin protein changes on cell cycle, proliferation and differentiation.

4) Identifying the effects of exposure to teratogens dysregulates normal embryonic development.

Funding Sources:

1. NSF CAREER Grant , Functional Analysis of Crest EffectorS (FACES), 2143217 (2022-2026)

2. NIH NIDCR R03 Grant, Mechanisms of microtubule-mediated cranial neural crest EMT and differentiation, DE032047-01 (2022-2024)

3. RSCA Scialog Advanced Bioimaging, MRI with molecular specificity for a new realm of neurodevelopmental research (2022-2023)

The videos below are from my most recent publication: Sip1 mediates an E-cadherin-to-N-cadherin switch during cranial neural crest EMT. JCB. C.D. Rogers, A. Saxena, M.E. Bronner. December 2, 2013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305050.

|

This video depicts a normal avian embryo. The green cells are cranial neural crest cells (injected with a control morpholino) migrating laterally away from the neural tube.

This video depicts an avian embryo lacking Sip1. The green cells are cranial neural crest cells (injected with a translation blocking Sip1 morpholino). These cells have completed the first phase of EMT (detaching from the neural tube), but are unable to complete EMT and separate from each other.

|

This video depicts a normal avian embryo. The green cells are cranial neural crest cells (injected with a control morpholino and membrane RFP) migrating laterally away from the neural tube.

This video depicts an avian embryo lacking Sip1. The green cells are cranial neural crest cells (injected with a translation blocking Sip1 morpholino and membrane RFP). These cells have completed the first phase of EMT (detaching from the neural tube), but are unable to complete EMT and separate from each other.

|